AI’s Impact in My Locality

Hello and welcome to the latest edition of my newsletter, Poiesis. This newsletter is where I share my research and practice relating to society and technology — AI, misinformation, surveillance, ethics, and more. It’s my way to help you understand and change the rapidly changing world of social technology.

In this edition, I want to uplift two fights against AI that are local to my life. First is a new data center being planned for construction in Monterey Park, near my neighborhood. Another is how faculty at my university are pushing back against the California State University’s uncritical adoption of ChatGPT Edu across the schools.

Finally, I’ll conclude by sharing out some sociotechnical philosophy I recently put out, making an argument about AI-based alienation through the lens of Martin Heidegger’s writing about industrialization.

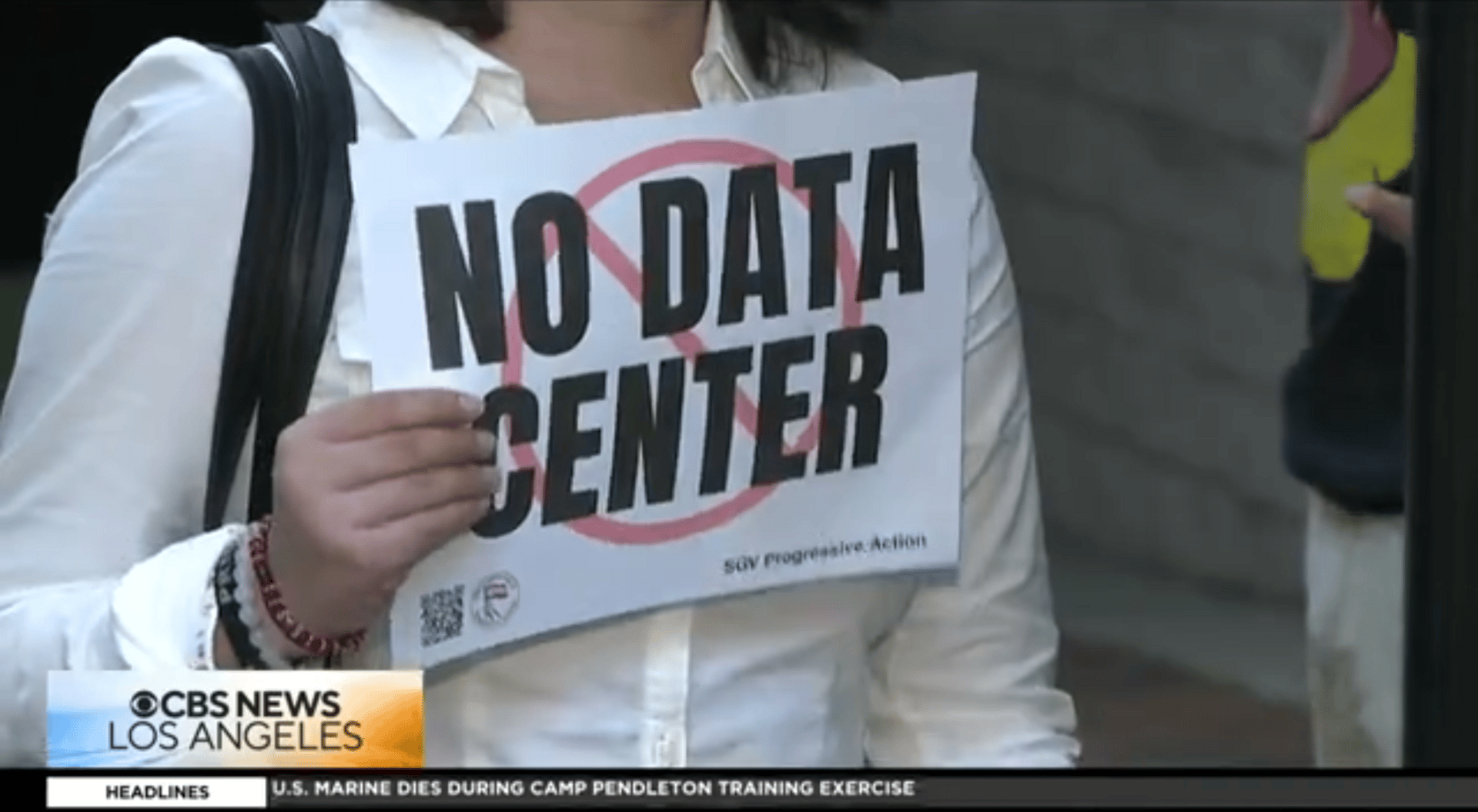

Residents Oppose the Construction of a Data Center in Monterey Park

Photo from CBS Los Angeles News Clip

On Wednesday of this past week, Monterey Park City Council held a meeting where residents could comment on the proposed construction of a new, 250,000-square-foot data center, including its own substation, and 14 diesel generators.

San Gabriel Valley (SGV) Progressive Action posted on their Instagram that the meeting was packed with speakers and comment cards opposing the construction. Instead of discussing the data center, the Council voted to delay the discussion until January 21st.

A map of Los Angeles, including Monterey Park to the east. Photo taken from Bing Maps.

There are several concerns stemming from the proposed construction. One major concern among residents is the environmental impact of the data center, as they have been widely documented as being extremely energy-intensive, requiring a great deal of water, and often polluting air in the process as their energy needs must be met by external fuel sources. The proposed Monterey Park data center is no different. It has been reported to include 14 diesel generators, which would lead to air pollution. SGV Progressive Action noted it will triple Monterey Park’s energy consumption. The same group also claims the city is avoiding a full environmental assessment, claiming the project “has no significant impact.”

I learned from my time in climate organizing that infrastructure projects that are undesirable and lead to pollution are often built in minoritized neighborhoods. Strategically, residents with less social status and power have a harder time fighting back. This is one of the key themes of environmental justice: poor people of color are predominantly the victims of toxic infrastructure.

I’m new to the LA area, so I wanted to see if this might be true in the case of the Monterey Park data center. I found this storymap, which provides a brief historical outline of redlining around LA County by Mirian Melendez — a reliable indicator in many major cities about which neighborhoods have historically been minoritized — as well as this article written by PBS SoCal on redlining. Redlining maps often still correspond with areas around cities that have less access to resources. Melendez notes in their report that redlined areas of LA — a great deal of South Central and East LA — still contain the largest populations of Black and Latine Angelenos as well as the most density of food deserts (defined as living beyond a half-mile from a supermarket).

1939 HOLC redlining map from PBS SoCal, courtesy of LaDale Winling and urbanoasis.org

A map of redlining overlaid on top of neighborhoods from Mirian Melendez’s “Redlining in Los Angeles, CA.” Monterey Park area is circled in red.

As this map indicates, Monterey Park is not in the most heavily historically redlined areas around LA, but as per the PBS SoCal map, it was classified as a mix of B- and C-grade. It is close to East LA, which is a clear area of intense redlining.

My partner has been recently reading the book Unassimilable, by Bianca Mabute-Louie, in which the author offers a manifesto of what it means to be in the Asian diaspora, drawing from experiences living in the San Gabriel Valley. Mabute-Louie writes about Monterey Park, noting that during the 1970’s and 80’s the neighborhood transformed from a white-majority area to an Asian-majority area, writing that “as of 2010, almost two-thirds of Monterey Park and it’s surrounding suburbs… were Asian American.”

None of this is to provide any conclusive points, but simply to point out that the project was not chosen to be built in a white, affluent neighborhood.

I hope to keep up with the community action against the data center as new developments occur. As AI is being pushed more and more as an economic driver for the U.S., many of us will become directly affected by the infrastructure constructed to support the craze.

Faculty and Instructor Resistance to AI-EdTech at the CSUs

I wrote briefly in a previous newsletter about work I’ve been conducting at Cal State LA (where I hold my postdoc) to organize faculty and instructors to critically think about AI’s role in education. Over the past semester, we have held several open reflection sessions, and I have had individual dialogue with a handful of instructors, spanning topics from AI’s effect on student learning to AI’s potential to fix the equity gap in education.

Recently, a few instructors at my university took action to present questions to the administration about the California State University (CSU) system’s decision to spend $17 million on ChatGPT-Edu licenses for faculty, staff, and students across all their campuses.

At many universities, there exists a body called the Academic Senate, a democratically-governed system of elected faculty who discuss important topics for the university, interface with administrators, and push for certain policies. My colleagues and I posed what’s called an Intent to Raise Questions (IRQ) at our Academic Senate. An IRQ is a way to pose questions that must be answered by the university’s administrators.

We decided to pose several questions about the decision to purchase ChatGPT-Edu:

1) What agreements / contracts are in place with AI corporations, including any of the companies reported as partners in the AI Initiative (Adobe, Alphabet, AWS, IBM, Instructure, Intel, LinkedIn, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and OpenAI)? What did we purchase from them? What were the costs? If there are contracts, what are the contract terms/ start and end dates? What termination clauses are there?

2) Who made the decision to purchase and roll out ChatGPT Edu for the CSU campuses, and how were those decisions made?

3) There was a CSU “Generative AI Survey” that closed on October 6th. What were the results of that survey? Will the data from that survey be made available publicly, or at least to the CSU campuses, and when? (please note that this survey was administered well after CSU’s “innovative, highly collaborative public-private initiative” to purchase and adopt AI technologies)

4) What data and evidence support Chancellor Garcia’s claim that “[CSU’s unprecedented adoption of AI technologies] will elevate our students’ educational experience across all fields of study, empower our faculty’s teaching and research, and help provide the highly educated workforce that will drive California’s future AI-driven economy?”

5) What specific strategies were in place to ensure “impactful, responsible and equitable adoption of artificial intelligence” before rolling out ChatGPT Edu to the CSU campuses?

6) What precise jobs is the CSU preparing students for in undertaking this initiative with the Tech/AI industry giants? How will the availability of ChatGPT Edu to our students help us prepare students for such jobs?

The questions were accompanied by a lengthy context, which I wrote for the IRQ, outlining research I’ve been conducting over the past semester related to AI in higher education. It includes results from meta-analyses and literature reviews into the effects of GenAI in education, arguments about the environmental impact, psychological impact on students, as well as evidence emerging about AI’s impact on the workplace. I posted the IRQ and context in a recent blog post so you can read the full text.

The long and short of the conclusions from my research are that the effects of GenAI, particularly chatbots, in higher education, are inconclusive. Several reviews and meta-analyses find that there can be positive effects on student outcomes. But they also warn that there are pitfalls: loss of student connection and relationships, reducing deep cognitive processing, and it can lead to worse outcomes if careful scaffolding of student-AI interaction is not present. Then, these potential positives exist alongside many negatives: huge environmental cost, model issues like hallucination and sycophancy, potential for psychological damage to students, and an unprecedented level of corporate control over education.

We are awaiting a response from the administration. I hope to share the response out once we hear, and additionally hope that administration agrees that we can approach AI in education with nuance and in an evidence-driven manner.

A More Philosophical Lens: AI and Alienation

As an interesting conclusion to this edition of the newsletter, I thought I’d share a Reel I recently made discussing AI and labor through the perspective of Heidegger’s arguments in The Question Concerning Technology.

For those who aren’t familiar, Martin Heidegger’s essay on technology focuses on how industrialization, leading to what he calls “modern” technology, radically shifted what it means to be a human producing artifacts in the world. He argues that before industrialization, production necessarily involved people having a relationship to the world — knowing where materials came from, working with them with their hands, being part of the world. Modern technology, post-industrialization, moved production into the factory towards mass production, which saw less relationality between individual producers and consumers and things that were produced. Heidegger argues that modern technology has brought about a massive alienation, a distancing from the physical world borne from viewing it more as a means to an end rather than an end in itself. If you want to learn more about this, I made a video about this a very long time ago, or you could check out the podcast Philosophize This! for its episode on Heidegger and technology.

I mapped this argument onto AI, which is being argued to stand to radically reshape production. I agree, partially, that AI is already reshaping production, but at this stage more so the production of social and cultural artifacts: text, video, images, ideas. In the education world this is very apparent, as students are turning in AI-generated essays — a significant change in the production of “ideas.” In this Reel, I argue that AI-production could alienate us in very similar ways to how Heidegger argues industrialization alienated us from the physical world. In this case, we are poised to alienate ourselves from the world of sociality, culture, and ideas.

Imagine a future where AI is so central in the economy of idea and content production that we are mostly feeding it prompts or directions to create cultural artifacts. Most people’s jobs will not revolve around using their own brains to do this production. Perhaps there would be a small minority who retain the ability to sustain themselves while using their brains. Capitalism’s competitive pressures would inevitably push everyone to incorporate AI more and more into the process of production (as we are already seeing).

The consequences of such a future could be profound. Just as we are alienated from the physical world, we could see a similar alienation from the cultural and social world. That could be psychologically damaging, as we lose a core part of our humanity that lies in creativity, struggling to produce art, video, photo, writing, ideas. The alienation comes from the profound objectification of culture and sociality that would result from widespread AI-driven production. Similar to how industrialization led to objectification of the physical world, AI-production would lead to objectification of ideas and culture, seeing them more as a means to an end rather than an end in themselves.

To be fair, this has already been happening to a large degree. Think of the drives to commodify content to the point where if your art can’t make you money, you cannot produce art. Or think of Zuboff’s Surveillance Capitalism, where companies are already pushing more and more to profit off of human experience and behavior, thus viewing these things as raw materials to feed into their behavioral prediction and advertisement machines. AI is simply poised to supercharge this process, as it enables production of these types of artifacts at an unprecedented speed and scale.

What do you think about applying Heidegger’s lens to AI?

This newsletter provides you with critical information about technology, democracy, militarism, climate and more — vetted by someone who’s been trained both as a scholar and community organizer.

Use this information to contribute to your own building of democracy and fighting against technological domination! And share it with those who would be interested.

Until next time 📣